Come, come to New Zealand, land of pristine wilderness and rugged adventure, say the adverts. So everyone comes flocking. And now it’s difficult to get a view of any glacier or lake for all the tourists posing for photos in front. Conversations with other travellers usually involve some complaint about how many tourists there are (without a hint of irony). Tourism is New Zealand’s main industry and it really does feel industrial, like we’re being managed, farmed, harvested, and are domesticating the landscape. But there is a reason everyone comes here, and it’s not hard to find your way off the main track and into the wild.

The first thing I noticed, and still can’t get over, is the colour of the water: bright turquoise rivers and lakes glowing with mineral energy, or icy grey rivers flowing with the milk of glaciers. Quite different from the crystal turquoise waters of Tasmania. Behind the water always lie mountains – the real things (they put Australia to shame), with snow-capped peaks, and growing at meteoric rates.

At the foot of Aoraki/Mt Cook, the tallest mountain, I think I found a lost paradise: a glade of raspberries, redcurrants and gooseberries among foxgloves, lupins and tall grasses, encircled by lichen encrusted trees. In the distance stood the glassy peak of Mt Cook, and as I gorged on fruit in the sunshine, the valley rumbled with the thunder of falling ice.

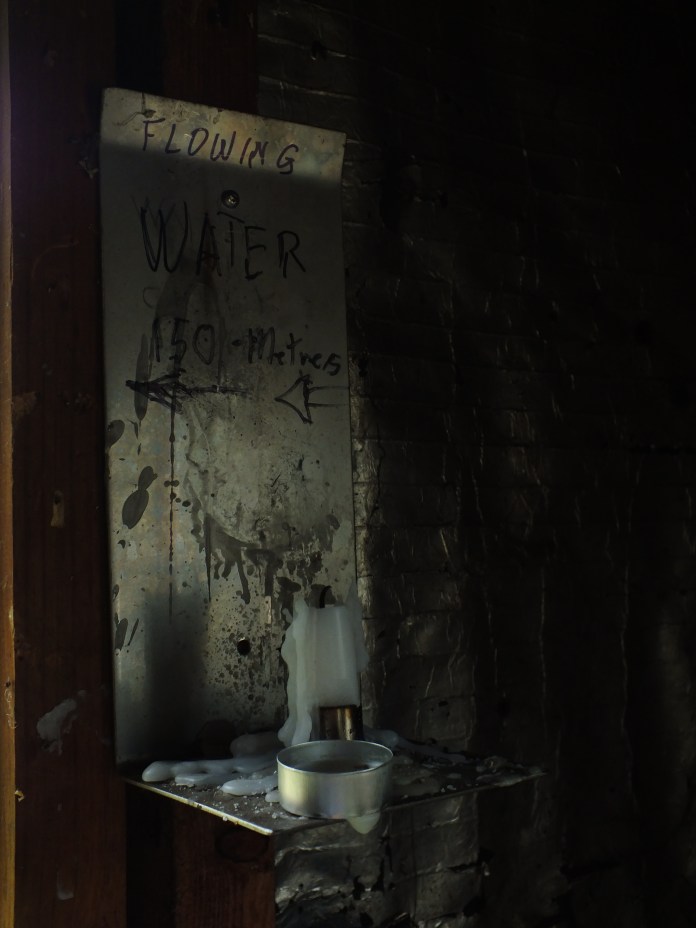

That night, camping below the mountains, the wind picked up and a gale grew. My tent billowed and shook, the roof pressing down to brush my sleeping bag, the walls huffing and puffing with the exertion of staying up. Sleep was impossible. A loud, distant roar would anticipate ferocious gusts. All I could do was lie there and hope my weight would stop the tent blowing away. In the morning I took cover in a nearby shelter where the people whose tents had broken were sleeping. It was no hurricane, but I’ve never felt winds like them: inside the shelter, the wind through the air vents was enough to blow out my stove, and the draft coming up the toilet was enough to stop you needing to use it. What, I asked a lost-looking climber, can you possibly do in weather like this? Go to the pub. So I got the first lift out as fast as I could.

This is what most of the views have actually been like:

The weather this summer has been foul (they promise it’s not normally like this). Rain, wind, rain, wind, rain, wind. There’s something apocalyptic about it. The world’s storm is hitting hard, the glaciers are disappearing. But it feels somehow appropriate for New Zealand, which rose from the waters through earthquakes and volcanoes. Before the arrival of people, everything that grew here blew here or flew here. It’s a world of ferns, mosses and exotic birds.

Fleeing the chaos of holiday parks and campervans for the rainy calm of the forest, I took a boat across a small river and began an overnight walk, with only the birds for company. Fantails would nervously hop closer and closer, peeking out from behind branches until we were staring at each other in silence. The path became flooded and walking became wading. I reached a river and saw orange markers telling me to cross it. There was no bridge, but the markers were unmistakeable. I held my camera up high and walked in up to my waist, feeling exactly like the adventurers I dreamed about when I was nine, with my pack on my back and explorer’s hat on. Then as I was climbing up the river bank I realised I’d forgotten to take out the pieces of paper in my pocket, including my map. So much for being the proper explorer.

There’s a fantastic system of backcountry huts right the way across New Zealand, often beautiful wooden sheds with fireplaces and plenty of candles. This one was at the edge of the forest by the shore of Lake Manapouri, and I had it all to myself (and the mice). The next day I had to cross a three wire bridge across a large river, a kind of tightrope walking exercise with the help of handrails. It was so much fun – and the sort of thing people pay tons of money for on their kiwi adventure tours, but here I was having my own proper little adventure all for free, in the real wild and with no safety protection at all!

The next hut was a real hunting hide out and full of gun magazines. I headed up towards a lake and my meditation was interrupted by a half-eaten rat, feet poised in a crouching position and tail alert. I froze, then noticed a pair of pale blue eyes peeping out from the grass. A small kitten lay there, terrified. How the hell did a kitten get there – it’s miles from anywhere, across a river, and there aren’t supposed to be any mammals here. I continued on, wondering how I could believe what I was seeing. And then I came across a massive green skull (a moa skull, from that giant extinct bird?!), and was convinced I was hallucinating. Too much isolation, too many berries, too much water in my shoes. There are all sorts of rational explanations now of course, but it was a useful excercise in self-doubt and challenge to empirical norms. I think I must be absorbing the land mysticism which is so much a part of modern Kiwi culture. It’s a strange country and we’re doing strange things to nature.